For over a hundred years, the doctrine of collective security has been circulating in diplomatic corridors. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2022 dealt a severe blow to the concept. The collective security mechanisms included in the United Nations Charter have not worked. They turn out to be useless if the aggressor state, i.e. Russia, has a veto right to block their launch. Substitutes for collective security included in the OSCE framework (the so-called principle of solidarity in the face of violations of OSCE norms and principles) did not work. Even NATO was not ready to act as the guarantor of collective security (following the example of the operation against Serbia in 1999), because it did not want an open conflict with Russia, which would risk causing a nuclear war. Ukraine had to face Russia alone in the physical and military dimension. But it enjoyed broad support in the West (supplies of military equipment, humanitarian aid, introduction of sanctions against Russia), although most of the developing countries decided to stand at the sidelines. However, if we treat Russia’s war against Ukraine as an experimentum crucis, the achievements of collective security in Europe turned out to be ineffective. For the UN and the OSCE the assessment should really be dramatic.

May Western politicians be able to draw the right conclusions from this.

The essence of the collective security doctrine is the recognition that in the international environment, violation of the applicable rules has a negative impact on the security of each member of the community (the principle of indivisibility of security) and requires collective action. Therefore, in order to establish collective security, it is necessary to catalogue norms and rules, as well as mechanisms for assessing the behaviour of states and reacting to violations of established norms. And most of all – it is required to develop an imperative of solidarity in the event of violation of the rules.

President Woodrow Wilson is considered the father of doctrine, in America at least. He became the President of the United States charged with academic knowledge and inspired by lofty ideas. He brought America into World War I not only to stop Germany and then help Europe restore the balance of power as it existed in the post-Napoleonic era, but to radically rebuild the mechanisms of international politics. He wanted to purge the international order of the habits of power politics to ensure the triumph of democratic values. Wilson’s idée fixe in international politics was to introduce arbitration as a universal means of resolving disputes and preventing wars. He wanted to demonstrate his new approach to diplomacy by negotiating US arbitration treaties with foreign partners. And more than thirty of them were negotiated before the outbreak of World War I. However, none has been launched in practice. Not that the idea itself was bad. But undoubtedly too idealistic for practical application at the time. Anyway, the fear of arbitration persists to this day. Because in politics, the principle still applies that the court is a court, but justice must always be on our side. Especially in territorial disputes. (Ukraine had the courage to agree to the resolution of its dispute with Romania over the delimitation of waters and the shelf around Snake Island by the International Court of Justice, which granted most of the disputed area to Romania in 2009. But this is a rare case. Russia claimed after 2014 that the annexation of Crimea was in accordance with international law, but it never turned to the Hague Court for a verdict. It knew it would lose.)

During World War I, Woodrow Wilson promoted the idea of an international system based on values. Its pillars were to be the principle of peaceful settlement of disputes, the principle of self-determination of nations, as well as the democratic responsibility of governments (rejection of “arbitrary” governments), and their implementation was to be achieved by building a “community of power”. The unpredictable and spontaneous system of responding to challenges and threats would be replaced by a rigid and transparent system forcing all participants to cooperate. Stability would be guaranteed not by ad hoc coalitions determined by the occasional common denominator of particular interests, but by a rigid, algorithmic mechanism of cooperation.

The League of Nations became the apotheosis of the Wilsonian vision of collective security. But it turned out to be a weak body and doomed to atrophy. The League of Nations’ death taint from its earliest days was the absence of the United States. This thwarted its aspirations to be universal. And a collective security system will not work if it is not a universal system. The problem was all the greater because the United States was then not only the greatest economic power in the world, but also the originator of the entire undertaking, i.e. the League of Nations. So no one felt responsible for its success. Great Britain had to some extent invested most in the political sense in the League, but not so much to build its policy in the interwar period on the principle of collective security. Thus, there was an institution of collective security, but its members did not want to, or could not, pursue a policy of collective security.

The absence of Germany and the USSR further weakened the mission of universality. And the abrupt withdrawal of Germany from the League in 1933 (after only seven years of membership) meant that it was treated as a flower in the fur of the European Realpolitik system.

On paper, the League of Nations was structured as an excellent collective security mechanism. Article 11 made every act of war or threat of war a concern for the entire League and gave it the right to take action that would secure peace. And the Briand-Kellog pact of 1928 outlawed war, or more precisely, resorting to war as a means of resolving disputes.

In order to avoid discrepancies around the definition of an act of war, an effort was made to define aggression, which was reflected in two conventions of July 3 and 4, 1934. The act of aggression was a declaration of war, an invasion of armed forces on the territory of another state, an attack by land, sea and air forces, sea blockade, supporting armed bands operating in another country.

The League of Nations was paralyzed by the lack of the ability to share the perception of threats, the lack of identification of the leading members of the League with what they considered peripheral or non-systemic threats. When Japan occupied Manchuria and other parts of China in 1931, an attempt was made to pass a resolution demanding the withdrawal of Japan from the occupied territories. After a year of deliberation (overshadowed by the Japanese threat of vetoing it), the invasion was condemned, but without any call for retaliatory action. Japan, on the other hand, left the League without any further ado.

The League turned out to be similarly powerless after the Italian invasion of Abyssinia. No serious action took place (also because certain politicians in London and Paris were under the illusion that Italy could be prevented from entering into a close alliance with Nazi Germany). And Italy left the League of Nations in 1937 anyway.

When Germany occupied Austria in 1938, and then Czechoslovakia, and Italy in 1939 occupied Albania (Italy-occupied Albania withdrew from the League of Nations by itself), the League of Nations was completely irrelevant. Chamberlain’s infamous dictum about the futility of starting a war over some quarrel in a distant country was an obituary for the European system of collective security. For the credibility of the system lies precisely in its readiness to act in the event of such quarrels in small and distant countries. The outbreak of World War II was noted by the League incidentally, only ex post in its annual report. It is significant that the prerogative of the League to remove the state guilty of aggression was used only once. On December 14, 1939, the USSR was expelled from the League of Nations after its invasion of Finland

The United Nations, established in 1945, was expected to learn from the failures of the League of Nations. First of all, it assembled all the victorious powers, including the USA (and, of course, the USSR). Its mandate and structure reflected Roosevelt’s concept of “world policemen” in which great powers were to be the guarantors of peace and collective security. The Charter of the United Nations thus placed the responsibility for maintaining peace on the Security Council, authorizing it to take mandatory measures to be applied by all members of the organization. And it ensured the universality of membership. At the same time, it gave guarantees to the great powers that it would not act against their interests. It gave them the right of veto.

The United Nations, however, only functioned effectively as a collective security mechanism in Korea in 1950 and in Iraq in 1991 (after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait). Military operations under the UN banner in Korea were possible because the Soviet delegation did not use the right of veto when boycotting the Security Council meetings. During the Cold War, the activities of the Security Council became hostage to the global confrontation of two world camps. The UN was unable to prevent the acts of aggression. All that was possible was to involve the United Nations in conciliation and stabilization activities (in Palestine since 1948, in the Golan Heights since 1974, in Cyprus since 1964, in India and Pakistan since 1949, and in over half a hundred other places).

The end of the Cold War has reawakened hopes for the creation of a United Nations capacity to provide collective security. In Prague, in November 1990, US President George Bush announced a new world order, the idea of a “community of freedom” based on the principles of freedom and governed by the rule of law, with a strong moral backbone. Open to everyone and, over time, to cover the whole world.

The operation under the aegis of the United Nations in Iraq in 1991 was to mark a new beginning in the activities of the United Nations for collective security. However, the reality quickly verified the aspirations. The United Nations proved to be functionally unprepared to contain internal conflicts, civil wars, which have become the main, if in many places not the only threat to international peace and security. And the interests of the great powers – the United States and Russia – began to diverge in opposite directions again, making the resolution of internal conflicts (for example in Syria today) dependent on the political relations between the great powers.

The weakness of the United Nations prompted the idea to base the collective security system on collective defense mechanisms, such as NATO, which was tried in practice in connection with Serbia’s actions in Kosovo in 1999. And it was suggested that NATO itself should be operationally given a global dimension (in the context of its involvement in Afghanistan and the takeover of command of the UN-authorized ISAF forces in 2003).

Of course, common security does not equal the alliance in terms of the guarantees offered, because the alliance is based on a specifically formulated threat and a specifically anticipated response. Even if the alliance does not have an absolute obligation to provide military assistance enshrined in its legal acts, such readiness and the ability to react together is highly implicit. Threats in the doctrine of collective security are abstract, not subjectivized. Violators are not defined a priori. And the state’s readiness to get involved in the name of removing the threat is not guaranteed by definition. The alliance is based on a common perception of threats, common security – by no means necessarily.

In the seventies, in the context of European détente, the concept of cooperative security emerged. This was the idealistic perception of the direction of the evolution of the system of norms and mechanisms of cooperation created as part of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. These ideas could no longer be exposed to such serious tests as, for example, the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 or the intervention of the Warsaw Pact troops in Czechoslovakia in 1968, but the introduction of martial law in Poland in 1981 caused a serious crisis at the CSCE forum. And it required to revise expectations as to the use of its possibilities.

The idea of cooperative security was revived in the early 1990s. CSCE/OSCE was again perceived as a field for building a European system of collective security. However, it failed to prevent the outbreak of numerous internal conflicts (in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova and others). And the resurgence of Russian imperialism has made it impossible not only to resolve some of these conflicts up to now, but also provoked open acts of aggression against other countries (the annexation of Crimea and support for Donbas separatism in 2014, the invasion of Ukraine in 2022).

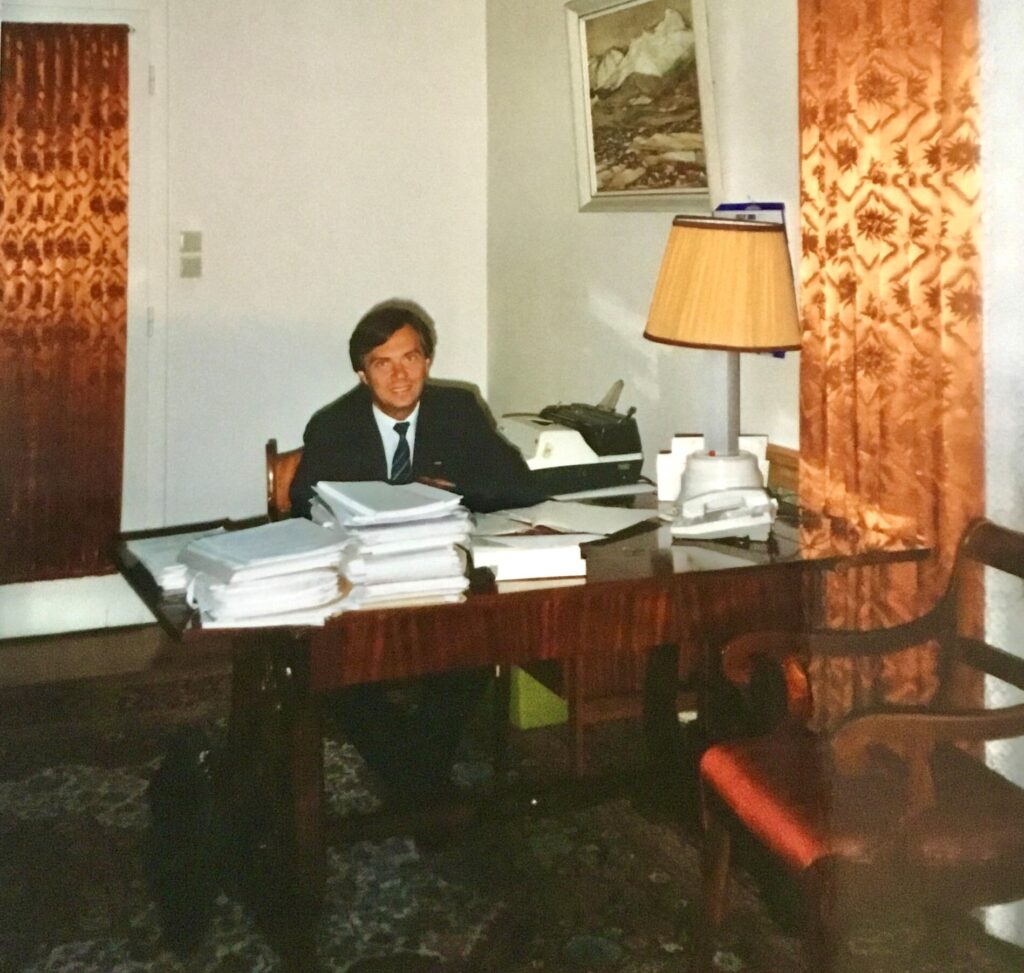

In the early autumn of 1992, my time was filled with work on the Polish draft of the Code of Conduct of States in the Field of Security as part of the CSCE process. My writing was going smoothly, but I decided to wait for the West to work out its proposal. In October, however, I received a confidential message that there would be no Western proposal. One of the Western European diplomats admitted that they wanted the Code to be the first important political document sponsored by the European Union (formally then the Community). But the idea was blocked by the Americans (through NATO channels). The Polish project could therefore take into account several ideas important for Western Europe. And help convince the Atlanticists that the European Community should, after all, submit its proposal, and convince the Americans themselves (Washington decision makers) that the game (the development of the code) is worth the effort. Informally, we were constantly encouraged to submit a draft, which of course only motivated me to work.

From the Polish point of view, the most important was the introduction to the text of the Code of the provision that each state has the right to choose arrangements in the field of security: to be a member of a military alliance or not, or to assume the status of neutrality. It was about preparing the field for NATO enlargement. Russia has, of course, contested these proposals. It interpreted the provision about not strengthening one’s own safety at the expense of the security of others in a specific way. It went back to its then rhetoric again at the end of 2021, demanding new security guarantees, i.e. Ukraine’s resignation from its aspirations to join NATO.

For me personally, the most important part of our proposal was the so-called the solidarity clause, which required joint and concerted actions by states in the event of violations of CSCE norms and commitments. It was undoubtedly one of the last attempts to give the CSCE the characteristics of a collective security organization. From today’s perspective, when one can see the powerlessness of the institution in cases of a flagrant violation of its principles, for example by Russia towards Ukraine, it can be assumed that our proposal was a manifestation of extremely naive idealism.

Americans reluctantly but accepted the idea of the Code, but on the categorical condition that it would remain a purely political declaration. In November 1992, we submitted the Polish draft in Vienna (proposals were also submitted by others, including, finally, even by the European Community), and in the spring of 1993, I was elected the coordinator of the negotiation work. However, I quickly had to resign from this role, because in September 1993 I was entrusted with the duties of Senior Diplomatic Adviser to the first Secretary General of the CSCE. The role of coordinator was taken over by Adam Kobieracki, later ambassador to the OSCE and NATO Assistant Secretary General, and he efficiently managed to finalize the adoption of the Code at the CSCE summit in Budapest in 1994.

Europe is still far from meeting the requirements of collective security. Will the Russian aggression against Ukraine serve as a catharsis and force the West to strengthen collective security mechanisms?

Collective security can emerge in two ways. The first is the noble way when it is a result of the operation of good virtues and shared values. This is how Kant described the emergence of the peaceful federation of states. The European Union is undoubtedly a community of good, Hesperian virtues and values. Belonging to it means being ready to resolve disputes only through peaceful means. Collective security in Europe can be achieved through the geographic expansion of this community. Or at least the adoption by European partners of common values, i.e. democracy, the rule of law and human rights.

The second way and the only one in the conditions of the existence of “vicious”, “aggressive” and “rogue” states is to introduce the desired patterns of behaviour under the fear of coercion and severe sanctions. This was how collective security operated under the sign of the Holy Alliance. But it is possible only when there is a sufficiently strong state – the agent of coercion and it has the appropriate political will. Not necessarily a gendarme, but undoubtedly an emphatic leader, ready to engage its forces to guard the established order. Basing the global collective security system on the Pax Americana concept has proved insufficiently effective. And the tensions on the West-China and the West-Russia lines made it impossible for years to develop a politically coherent collective identity within the UN. And there is no and there will be no collective security without collective identity. Even if it had to come from the community of fear.